James Leyburn’s book The Scotch-Irish. A Social History (1963) traces the migration of the Scotch-Irish in the 17th and 18th centuries. The earliest spelling of our McCollough surname in the 1770s to 1790s by Captain John McCollough, his father John, and his grandfather Gerhardt Fiscus suggests that our McCulloch ancestors in the Lowlands of Scotland moved to Ireland for several generations before coming to America. We don’t know for certain, but Leyburn’s history traces the likely pattern of movement our McCollough ancestors.

On a clear day, one can see the hills of Ireland from the old McCulloch estates and farms on Mull of Galloway in southwest Scotland. From here, Ireland is only a scant 20 miles across the Irish Sea. Traders travelled back and forth across the narrow straights for thousands of years.

In 1600, conditions for the tenant farmers in the Lowlands of Scotland were hard and plagued by famine, disease, and poverty. At the same time, England was looking for a way to solve the Irish “problem.” Ever since the Norman king of England Henry II invaded Ireland 400 years earlier, the native Irish resisted colonization. Ireland was a steady drain on royal wealth and the military. The peasant farmers suffered in Ireland under English rule as they did throughout much of Scotland.

In the early 1600s, King James I of England (VI of Scotland) launched an ambitious plan to subdue the rebellious Irish in Ulster, the northernmost province of Ireland by taking the land from the native Irish and establishing English “plantations.” Two Ayreshire (Scotland) lairds, Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton, became large plantation holders in Ulster, but others received lands as well. In 1606, the King established a similar plantation at “James”town in Virginia.

The King and plantation owners needed a source of colonists, and the Lowland Scots were ideal candidates. Many McCullochs and related families, especially the less fortunate, had an opportunity to leave their depauperate condition in Scotland and begin a new life in the Ulster district of Ireland. The plantations replaced the need for an English army in Ireland and lessened poverty in Scotland by draining off some of its surplus population.

About 250,000 acres in Ireland was parceled out to “undertakers,” the Scots and English gentry who agreed to “plant” their new Irish estates with Protestant farmers. The Lowland Scots became the mainstay of the Plantations. The Lowlanders, including the McCullochs, would have a great advantage, since they “lye so near to that coiste of Ulster” that they could transport across the Irish Sea their “men and bestiall.”

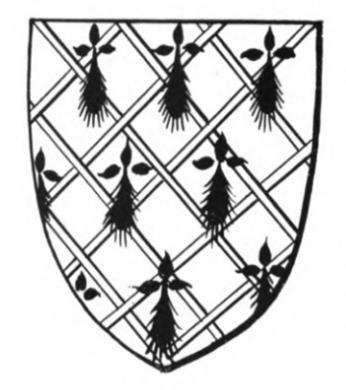

During this time, some of the McCulloch estates failed under mismanagement or misbehavior. But at least one of the McCullochs from Scotland was an “undertaker,” and undoubtedly many more moved to Ireland to lease land on plantations. In 1609, James McCulloch (son of Robert) became a landlord (undertaker) in the plantation of Ulster, taking up 1000 acres. His lands were known as the Manor of Mullaghveagh in County Donegal. Many of the Scottish undertakers did not stay landholders in Ireland for long and sold out. James McCulloch sold his interest in 1612 and returned to the Drummoral estate in southwest Scotland.

Undertakers typically received 2000 acres and agreed to bring 48 able men and their families. Lowland Scots could sign up for a lease for 21 years or life. Of the 6 counties in the Plantation, the Scots settled mostly in Down, Antrim, Donegal and Tyrone. They left their feudal past and formed new neighborhoods, established Presbyterian churches, and farmed the richer soil of the Irish countryside. During this period, the potato was introduced from America by Sir Walter Raleigh and became the mainstay of their diet. They had far more control of their destiny than they did under a feudal system in Scotland.

The Plantations attracted Scots families who had little to lose and wanted to improve their lot in life. By some estimates by 1640 there were over 100,000 Scots living in Ulster. They formed alliances with the displaced native Irish. Many intermarried. The plantationers needed farm labor and hired the Irish as subtenants. The Scots plantationers and native Irish maintained an uneasy alliance for a short period of time before bitterness and resentment resulted in a series of Irish uprisings starting in 1641 that lasted for 11 years. Tens of thousands of the Ulster colonists were killed. Cromwell came from England in 1650 and brutally crushed the native Irish and Scots colonists alike and brought the English Parliament to Ireland. Struggles between the Catholic and Protestant religions continued until King William of Orange defeated the deposed King James on Irish soil at the Battle of the Boyne.

By the late 1600s, the British control of Ulster was complete. Another wave of Lowland Scots came to northern Ireland during “the killing times” when the Covenanters (including many McCullochs) were persecuted in Scotland. English dissenters, including Puritans and Quakers, also fled to the relative peace in Ulster. Ulster became a mingling place for people of different Protestant backgrounds. Many of the English Ulstermen joined their Scots neighbors when the exodus to American began in earnest after 1717.

Most transplanted Scots lived in Ulster for 3, 4, or 5 generations before coming to America in the 1700s. By this time, they considered themselves more Irish than Scots. In the New World they would come to be known as the “Scotch-Irish.”